Surgery

If your doctor has reason to suspect that you may have cancer, you are likely to be referred initially to a surgeon. This is partly because, as already explained, some kind of surgical procedure is very often required to make a definitive diagnosis, and partly because surgery is the best treatment or the best initial treatment for many types of cancer. Where cancer is discovered, its extent may also be established in the course of an operation; sometimes this is an important aim of the procedure. Examples include armpit lymph node removal (a ‘sentinel node biopsy’ or ‘axillary nodal dissection’) for women undergoing surgery for breast cancer, and a thorough inspection of the abdominal cavity (during a ‘staging laparotomy’) for women undergoing removal of ovarian cancer.

It is only understandable that most people will feel nervous about having to have an operation. However, the overwhelming majority of cancer operations proceed very straightforwardly and satisfactorily. It is of course inevitable that the results are not always perfect, but it is not feasible to discuss in detail here the possible short- or long-term adverse effects of particular operations, which may vary from relatively minor procedures lasting a few minutes to major undertakings over many hours. A small number of patients may not be strong enough to undergo the surgery that would otherwise be recommended.

Some operations inevitably leave substantial long-term effects on appearance, function or both. Others carry risks of certain side effects for some patients, for example arm swelling (see ‘lymphoedema’) after axillary nodal dissection and impotence after surgery for rectal or prostate cancer. Any such risks will normally be discussed in detail with you beforehand, but if you feel you need more information don’t be afraid to ask for it.

Some patients only need to spend a very short time in hospital afterwards, others two or three weeks or even longer. Some are able to return to a normal lifestyle almost straightaway, whereas others may take some months to recover fully after major operations. Although most patients will feel some discomfort in the period immediately after the operation, they can nevertheless expect nowadays to receive a high standard of postoperative care including very good pain control.

Commonly used surgical terms

Resection

The removal of a tumour or organ; words ending in ‘-ectomy’ mean the same thing. For example, removal of a lung lobe containing a cancer may be called a ‘pulmonary lobectomy’ and removal of a cancer-containing prostate gland a ‘prostatectomy’. Removal of lymph glands that the cancer may have spread to is sometimes called a ‘lymphadenectomy’.

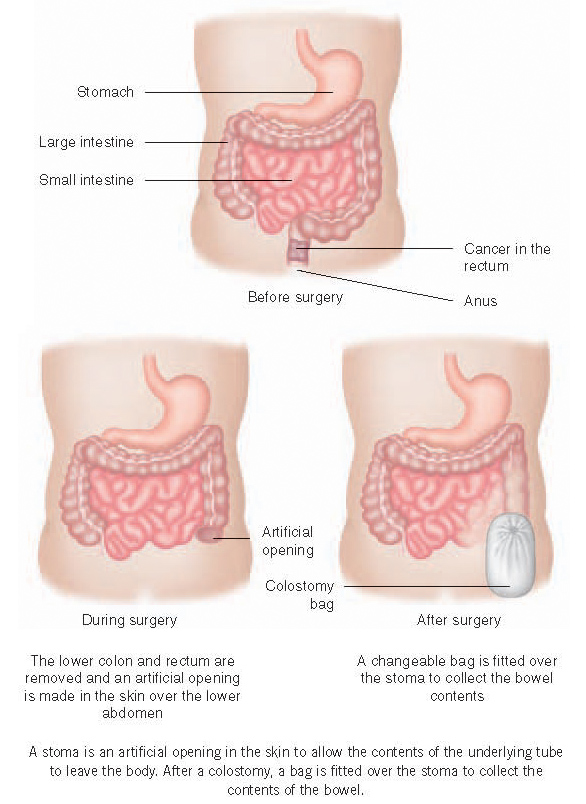

Words ending in ‘-ostomy’

When one of the body’s internal tubes is blocked by a tumour or when part of it has to be removed, the surgeon may need to bypass the obstruction and create an inlet or outlet by joining the tube to an artificial opening made in the skin (a ‘stoma’ – see below). For example, joining the wind-pipe or ‘trachea’ to the overlying skin is called a ‘tracheostomy’ and may be temporary or permanent, depending on the circumstances. Joining the end of the small bowel (‘ileum’) or large bowel or colon to a stoma in the abdominal skin are called an ‘ileostomy’ and ‘colostomy’ respectively. These too may be temporary or permanent.

Stoma

An artificial opening in the skin to allow the contents of the underlying tube to exit the body. After an ileostomy or colostomy, for example, a bag will be fitted over the stoma to collect the bowel contents, and modern designs enable the great majority of people who undergo this procedure to lead virtually normal lives.

Surgery for cure

In most cases, the surest way of eradicating a localised cancer is, where possible, to excise it (cut it out) with an adequate margin of surrounding tissue which may appear normal to the naked eye, but which may have been infiltrated by microscopic cancer cells. Such ‘radical’ surgery of course cannot cure a cancer that has spread to distant parts of the body, unless the metastatic cancer can also be dealt with. Sometimes, even though the cancer is indeed localized, compete removal turns out to be technically impossible because of the extent of infiltration into surrounding tissues or involvement of other vital organs. On occasions the surgeon may not know until the operation is underway whether he/she will be able to remove all the cancer.

Most cancer surgery is conducted as a carefully planned or ‘cold’ procedure, the diagnosis having already been made with near or absolute certainty. However, a small minority of people are first discovered to have cancer during an emergency operation made necessary by complications of the cancer, such as perforation or obstruction of the bowel. In this situation, the results of surgery unfortunately tend to be rather less good. This is because these tumours are quite often at an advanced stage and also because the person concerned may not be in good general health.

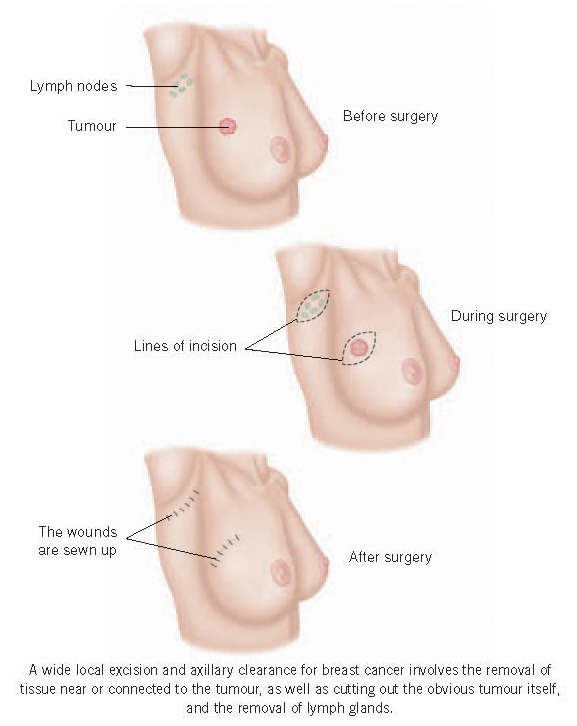

There has been a trend in recent decades towards less radical surgery for some tumours. For example, providing the size and position of the growth are favourable, it is often possible to remove a cancer from a woman’s breast, together with sufficient surrounding tissue (‘wide local excision’), while avoiding the need to remove the whole breast (mastectomy). This operation is then usually followed up with radiotherapy to the breast to get rid of any remaining microscopic traces of cancer, and the prospects for cure are just as good as with mastectomy. A similar combination of less aggressive surgery and radiotherapy can also be used to treat the much rarer soft tissue sarcomas.

In other situations surgery may be more extensive than might immediately seem to be necessary. For example, some women with breast cancer are advised to have a thorough removal of lymph nodes from their armpits, in addition to surgery to the breast itself. This is known as an ‘axillary nodal dissection’ or ‘axillary clearance’ and is quite often recommended if it has already been shown that cancer has spread to one or more lymph nodes (see ‘sentinel node biopsy’). Not only can this procedure eradicate any metastases that might be present in the nodes, it can also give useful information about the chance of the cancer having spread microscopically to other parts of the body. The risk of this increases the greater the number of lymph nodes that are involved. The results of the lymph node analysis can sometimes thus be used to inform patients on how advisable it would be for them to have adjuvant chemotherapy to maximise their chance of cure.

But an axillary clearance can carry a risk of arm swelling caused by lymphoedema and the sentinel node biopsy technique was developed with the main aim of avoiding this risk for patients who do not have involved lymph nodes. Fortunately we now know that not all patients with involved nodes need an axillary clearance. Recent research has shown that some women with smaller involved nodes can perfectly safely avoid further surgery, relying instead on drug treatments or radiotherapy to deal with any possible microscopic spread to the other nodes.

Laparoscopic and robotic surgery

Recent decades have seen a growth in the use of ‘key-hole’ or ‘laparoscopic’ surgery. The surgeon makes a small number of quite small cuts through the skin, through which an instrument rather like a telescope, a ‘laparoscope’, is inserted together with other small instruments necessary to carry out the operation. The procedure can take longer than conventional surgery but being less disruptive, it usually results in less pain and discomfort, a quicker return to normal function, a shorter hospital stay and fewer complications. This type of surgery is now routine, for example, for patients needing removal of a longstandingly inflamed gall-bladder, and it is being used increasingly for patients with some types of cancer. In experienced hands it seems to be as effective as conventional surgery for some patients with kidney, colon and prostate cancers.

Robotic surgery is a type of laparoscopic surgery where the surgeon is assisted by a machine or robot. The instruments are actually manipulated by the arms of the robot, but under the control of the surgeon who has an excellent view of the internal structures with high powered three dimensional magnification.

Surgery for metastases

Surgery has long been known as a potential cure for many people whose cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, but in recent years surgery has also been offered to increasing numbers of carefully selected patients whose cancer has spread more distantly via the bloodstream, to a localised fairly small and removable part of the lung, liver or brain. Sometimes chemotherapy will be given first with a view to shrinking the secondary cancer and making it more easily removable. There tends to be a better chance of success when there is a long interval between treatment of the primary growth and the development of the metastasis. However it is not uncommon for patients newly diagnosed with bowel cancer to have both the primary growth and one or a small number of liver metastases removed successfully at the same operation, or at separate operations a short while apart. Some liver metastases can be destroyed by heat, ‘radiofrequency ablation’, which involves inserting a probe through the liver tissue into the growth.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU)

This is another technique which utilises heat to destroy cancerous tissue. The heat is generated by a carefully focused beam of high-intensity ultrasound. This relatively new treatment is now increasingly been offered as an option for some men with localised prostate cancer. It is administered via a probe inserted into the rectum, under general or spinal anaesthesia. The evidence regarding its long term efficacy and side effects is at present somewhat limited and it has not yet been compared with standard therapies. But results so far suggest that it might be as effective as more conventional surgery and with possibly a reduced risk of some side effects.

Surgery to improve quality of life

Reconstructive surgery

Considerable progress has also been made in restoring appearance or function after operations to remove cancer. For example, many women who have had a breast removed are now offered surgery to create a ‘new’ breast, either by inserting some form of artificial ‘implant’ beneath the muscle underlying the skin, or by building up a new ‘breast’ using muscle and fatty tissue (a ‘flap’) from the back or lower abdominal wall. The results, although not perfect, are frequently highly satisfactory and quite often excellent. They can make a huge psychological difference for those women who understandably find it very difficult to live with the loss of a breast.

Such reconstructive procedures require considerable surgical expertise. This is provided by specialist breast or plastic surgeons. As well as contributing to the care of some patients with breast cancer, plastic surgeons perform a very important rȏle in helping to restore appearance and function after major surgery for cancers involving the mouth and throat and other nearby structures. Some reconstructive procedures are done at the time of tumour removal, with the plastic surgeon operating together with the surgeon who removes the tumour. Others may be done some time later.

The artificial material used in any form of reconstructive surgery is known as a ‘prosthesis’ Some people with bone sarcomas of the limbs undergo bone replacement prosthetic surgery after removal of the growth, avoiding the need to amputate the limb.

Palliative surgery

Surgical procedures are also performed to relieve symptoms. Sometimes this is in conjunction with other treatments aimed at destroying the cancer.

Prosthetic tubes or ‘stents’ may be inserted to relieve obstruction caused by a growth. This is often done for people with cancer of the oesophagus and sometimes for patients with rectal cancer. Obstructions within the abdomen are sometimes relieved by ‘by-pass’ operations. Metal prostheses may be inserted into a bone that has been fractured or substantially weakened by a metastatic tumour. This is known as ‘internal fixation’ – it restores strength to the bone and allows a rapid return of normal or near-normal use to the limb. Lasers are sometimes used to bore a hole through tumours obstructing the oesophagus or one of the major air tubes or ‘bronchi’ within the lung. A tracheostomy may be necessary when a tumour is obstructing the voice box or larynx and causing difficulty in breathing.

A tumour that is pressing on the spinal cord can cause leg weakness by interfering with the nerve supply to the muscles. This can sometimes be relieved by partial removal of the tumour by a neurosurgeon or orthopaedic surgeon. Some people with breast and prostate cancers benefit from surgical removal of their ovaries or testes, operations known respectively as ‘oophorectomy’ and ‘orchidectomy’. These cancers are very often susceptible to hormonal influences. Removing the sources of these hormones can bring about marked tumour shrinkage which often lasts for a long time, although these days the same effects are more commonly achieved with drugs which suppress hormone production. Finally, surgical procedures are also undertaken occasionally to control bleeding from a growth.

KEY POINTS

-

Confirmation of a diagnosis of cancer is usually established by some form of surgical procedure

-

Surgery cures more cancers than any other treatment used alone