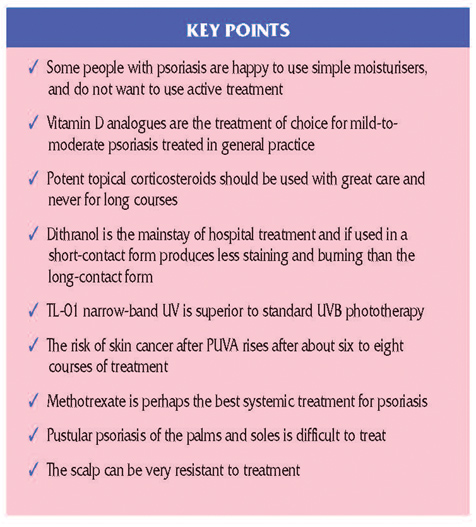

What treatments are available?

Not everyone with psoriasis wants treatment. In fact, once you know what psoriasis is, you may be happy to live with the occasional flare-up of a few patches on your elbows and knees and just use self-help measures such as complementary therapies. You may want to get skin preparations over the counter (OTC), buying them at the pharmacy as and when you need them. This is fine, once the diagnosis has been made and you are satisfied that you can handle the treatment yourself.

Stronger treatments are only available on prescription; some of these are not usually prescribed by GPs, but only by a hospital skin specialist (dermatologist), although, once the dermatologist has started you off on the treatment, your GP may be able to take over. Treatments that are offered only in hospitals are usually systemic in action, which means that they don’t just affect the skin, but affect the whole body.

The treatments will be discussed in this chapter under the following headings:

• Self-help: complementary therapies.

• Over-the-counter treatments (OTC): creams and ointments available over the counter from pharmacies.

• Prescription-only medicines (POM): topical treatments (applied to the skin or scalp) from your GP or dermatologist.

• Hospital treatments: systemic treatments – drugs taken by mouth or treatments that affect the whole body (for example, radiation treatments), usually from a dermatologist.

SELF-HELP

Complementary medicine

Many people with psoriasis try complementary therapies. This may be because conventional treatment has no effect on their psoriasis or because they are worried about the side effects of the treatments that they have been using. Undoubtedly, complementary treatments, such as acupuncture, homoeopathy and healing, can help some people. Relaxation therapies, such as yoga, are useful if stress is a common trigger of flare-ups. We don’t know how all complementary therapies work. In fact, some may help simply because you believe that they will (the placebo effect). It is important to remember that not all complementary therapies are entirely without side effects; for example, herbal products, particularly Chinese herbal medicines, are not all well standardised and can cause side effects such as liver damage. If you wish to try complementary therapies for your psoriasis, make sure that you consult a properly qualified practitioner.

OVER-THE-COUNTER TREATMENTS

Moisturisers (emollients)

These are available on general sale in many outlets, for example, in supermarkets and over the counter at pharmacies. If you need large quantities of moisturisers, you may find it cheaper to get them on prescription from your GP.

The regular use of emollients helps to relieve itching and scaling in psoriasis. Emollients smooth, soothe and hydrate the skin by sealing in moisture. Their effects tend to be short-lived, so they need to be applied regularly, perhaps three times a day. Light moisturisers, such as aqueous creams, are the easiest to use, but greasier preparations, such as emulsifying ointment BP, may be necessary for very dry skin or areas where cream gets rubbed off easily, such as the soles of the feet.

Emollients available over the counter include:

• Bath oil containing soya oil (Balneum bath oil)

• Creams containing liquid paraffin and white soft paraffin (E45)

• Creams containing glycerol (Neutrogena)

• Creams containing urea, which reduces scale (Nutraplus)

• Ointments (greasy) containing emulsifying ointment (Emulsifying ointment BP).

For many people with psoriasis, the loose silvery scale is the most embarrassing aspect of their condition, as flakes show up easily on clothes and carpet. A simple emollient can make the scale disappear, but it won’t get rid of the plaques, which remain red. You can apply emollients directly onto your skin (creams or ointments), put them into the bath (oils) or use them in the shower (gels). They are all safe to use in the long term and will generally cause no side effects. Very occasionally, however, you may be sensitive to one of the ingredients (particularly lanolin) and will need to change to another cream if irritation occurs.

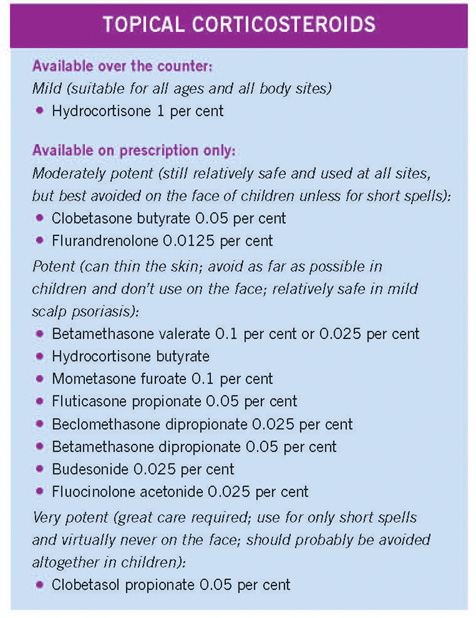

Tar products

There are numerous creams, ointments, bath products and scalp applications containing coal tar. Coal tar products (Alphosyl, Clinitar and Pragmatar, for example) reduce scaling and inflammation. They work by inhibiting DNA synthesis, which is necessary for cell multiplication, and therefore reduce the rapid turnover of skin cells.

Tar products have been available for many years. The original preparations could not be used on the face because they caused irritation, and many people disliked their strong, characteristic odour. However, newer products, such as Carbo-Dome, have a milder odour and can be used over the whole body. Coal tar baths can be very soothing for people with widespread psoriasis and are part of the Ingram regimen.

Most tar products are available over the counter, but you should discuss their place in the treatment of your psoriasis with your GP or dermatologist before you use them. Tar cannot be used in sore or pustular psoriasis because it will cause severe irritation. Other possible side effects include an acne-like rash and skin, hair and fabric staining.

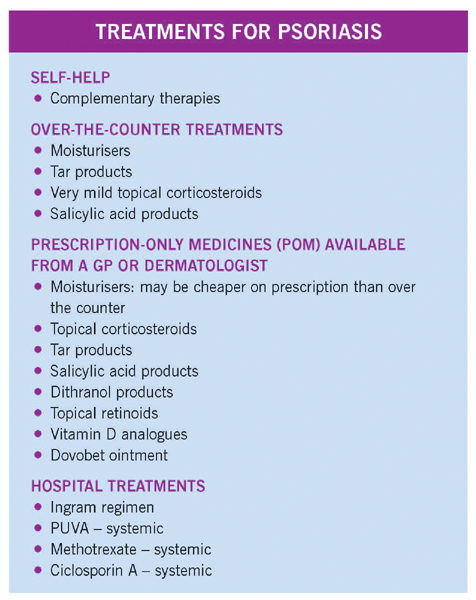

Mild topical corticosteroids (steroid creams and ointments)

You can buy weak topical corticosteroids (steroid preparations applied to the skin) over the counter as Dermacort, Hc45 and Lanacort. These preparations are available as creams or ointments and contain up to one per cent hydrocortisone, which is the weakest type of corticosteroid usually prescribed by doctors. Weak steroid creams may not have much effect on psoriasis and also have some drawbacks, so buying them over the counter is not really recommended. For more on topical corticosteroids, see ‘Prescriptiononly medicines’ below.

Salicylic acid

This is the active ingredient of aspirin, which helps to get rid of scaling. It may be combined in creams with tar (Pragmatar), dithranol (Dithranol paste BP) or tar and dithranol (Psorin). Although these creams have very few side effects, they may irritate or dry out your skin.

PRESCRIPTION-ONLY MEDICINES

Topical corticosteroids

These are steroid creams, ointments and lotions that are applied to the skin, rather than being taken orally as tablets. They have a vital role in the treatment of psoriasis because they work by damping down inflammation. You can buy weak steroids over the counter (see the previous section), but it is best to seek medical advice before using them as they can cause side effects.

For thick plaques of psoriasis, fairly potent corticosteroids are needed to gain benefit. However, these suppress the plaques, rather than clearing them completely. If topical corticosteroids are used constantly, a rebound reaction can occur – the plaques can worsen and may even change to pustular psoriasis. If potent corticosteroid preparations are used for many months, they can thin the skin permanently and even cause scars (called striae). In particular, potent corticosteroids should not be used on the face, in the flexures (creases) or on the genital area.

If potent corticosteroids are used over a widespread area of the body for prolonged periods, they may be absorbed in large-enough amounts to cause severe systemic side effects. These effects include high blood pressure, diabetes, thinning bones (osteoporosis) and Cushing’s syndrome (a condition causing weight gain, a moon face and acne). These reactions are fortunately very rare, and potent corticosteroids are not prescribed for extensive areas of the body for prolonged periods.

Another problem that occurs if potent topical steroids are used continuously is that, over a period of time, they become less effective. The body gets used to the strength of the cream and requires ever more powerful strengths to achieve the same result. A break in treatment is often required for them to return to their full potency. This effect is called tachyphylaxis.

Topical corticosteroids do have considerable benefit in psoriasis, and weaker products such as hydrocortisone can be used on the face, in the flexures and on the genitals with little risk of skin damage. The weaker steroids work well at these sites because the plaques here are usually quite thin. In addition, the corticosteroid is effectively absorbed into the skin because more moisture is present.

Potent corticosteroids are tolerated quite well on the scalp without much skin thinning and are useful for mild scalp psoriasis. However, if the plaques are raised and lumpy, they need to be thinned by other means before corticosteroids have a chance to work.

Vitamin D analogues

These are most important in the treatment of psoriasis. They are available on prescription only and are usually available from GPs. The analogues are available as calcipotriol cream, ointment and scalp solution, and tacalcitol ointment.

Vitamin D analogues are the treatment of choice for plaque psoriasis. In general, about one-third of patients do very well with almost complete clearing, one-third derive some benefit and one-third are not helped very much. The analogues work, at least in part, by causing the epidermal cells (keratinocytes) to divide in a more normal way and therefore produce normal keratin. They are relatively safe and can be used on children. Unlike topical corticosteroids, they do not thin the skin.

If excessive amounts of vitamin D analogues are used in very widespread psoriasis, a significant amount may be absorbed by the skin. This can increase the calcium content of the blood, which can damage the kidneys and cause widespread problems. However, if you limit to 100 grams of 50microgram strength calcipotriol, which is the usual prescribed weekly dose, you should not experience any problems. Vitamin D analogues can cause irritation, so don’t get them in your eyes; use them with care in the creases of your skin and on your genitals, where the skin is more delicate.

Dovobet ointment

Dovobet combines the vitamin D analogue, Dovonex, with a potent corticosteroid in an ointment base. The two ingredients enhance each other to give a greater effect than either used on its own. It is used daily for four weeks, and then needs to be discontinued to prevent steroid-induced thinning of the skin. It can be used again but only after a gap of about four weeks. It works well for most patients, but the psoriasis does tend to flare quite quickly in some patients, limiting the benefit for these patients, who end up with rather intermittent therapy. After using Dovobet, Dovonex should be used for any residual lesions or at the first sign of flare. Often, however, it is not sufficient to hold the flaring psoriasis.

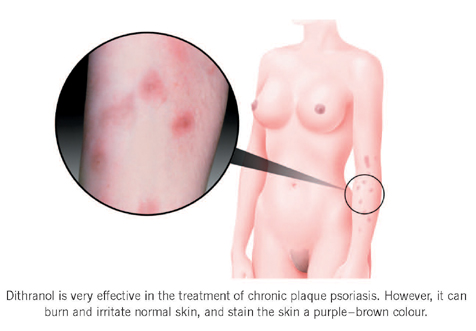

Short-contact dithranol

Dithranol is a highly effective synthetic compound, available only on prescription in various products, including Dithrocream and Micanol. It is very effective in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. It works by inhibiting the synthesis of DNA, therefore preventing the rapid cell turnover. The main problems with dithranol are that it tends to burn and irritate normal skin and can also stain the skin a purple–brown colour.

Almost 25 years ago, it was discovered that dithranol did not have to be left on the skin for 24 hours as previously thought; it could be removed after 10 to 30 minutes and still have a beneficial effect, but with much less staining and irritation. This short-contact dithranol treatment can be used by well-motivated patients at home under the supervision of their GP.

The product suitable for short-contact dithranol treatment comes in five strengths: 0.1 per cent, 0.25 per cent, 0.5 per cent, 1 per cent and 2 per cent Dithrocream. Patients should start at the weakest and move up in strength every two to three days, unless irritation or soreness occurs. Although dithranol is in contact with the skin for 30 minutes (the usual time of application), it will stain any clothing permanently, and contact with soft furnishings should be avoided. When washed off the skin, dithranol tends to stain baths or showers and should be cleaned off immediately. When dithranol is used correctly and carefully, about two-thirds of patients gain a satisfactory response, often with a remission lasting several months. The full Ingram regimen (see ‘Hospital treatments’) gives more complete and consistent results, but the short-contact method enables people to experience the benefits of dithranol at home. There is some evidence that, in the full Ingram regimen, the dithranol paste can be removed after two hours with the same results as leaving it on for 24 hours.

Topical retinoids

Topical retinoid creams are derived from vitamin A. Oral retinoids (described in ‘Hospital treatments’) are more powerful and more effective than the creams, but have far more side effects. Topical retinoids work by encouraging skin cells to mature properly, rather than dividing too rapidly and producing the poorly formed skin cells that make up the plaques. The major side effect is redness and skin peeling for several days after the cream is applied, but this usually settles with time.

The only topical retinoid used in psoriasis is tazarotene (Zorac). Tazarotene is used for mild-tomoderate psoriasis that covers less than ten per cent of the body. A number of retinoids are also available for topical use in acne and various scaly disorders.

HOSPITAL TREATMENTS (DERMATOLOGY DEPARTMENTS)

If your psoriasis is proving difficult to treat with more standard treatments (such as those described previously), your GP will refer you to a hospital skin specialist (dermatologist). There are also a few rare instances in which a particularly severe form of psoriasis requires urgent hospital admission. The specific treatment you are given depends on the type and severity of your psoriasis and what you have already tried.

Dithranol (Anthralin) in the Ingram regimen

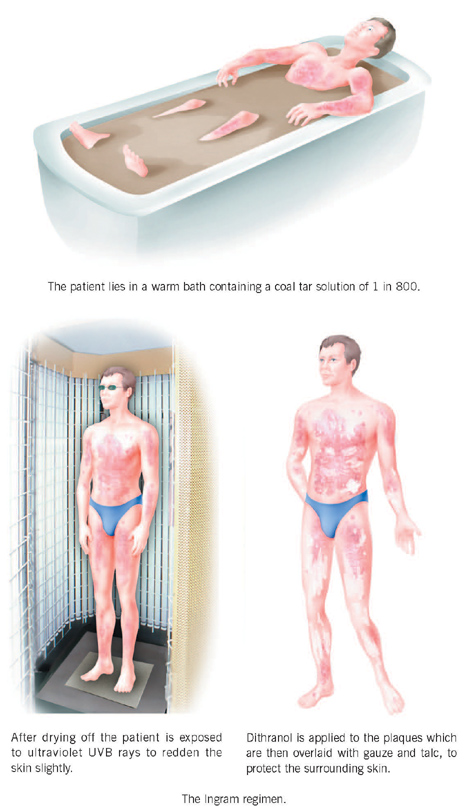

The use of short-contact dithranol is described in the previous section. Dithranol has been the standard hospital-based treatment in dermatology departments since the regimen was described by Professor Ingram in 1953. In many centres, it is used in outpatient units, but, in others, patients have to be admitted to hospital for treatment. The Ingram regimen involves lying in a warm bath containing a coal tar solution of 1 in 800. After drying off, you are exposed to ultraviolet UVB rays to redden your skin slightly. Dithranol is then applied to the plaques and covered by talc and gauze dressings to protect the normal skin. The whole procedure is repeated daily.

If you attend an outpatient unit, you’ll be treated five days a week; if you are an inpatient, you’ll probably be treated seven days a week. About 85 per cent of patients are free of their psoriasis after about 20 treatments, although some people’s skin will clear much sooner. Treatments can be repeated if necessary, but the exposure to UVB rays has to be limited to avoid increasing the risk of skin cancer.

The advantage of dithranol over many other treatments is that it is well tried and tested, and is very safe. Once the patient is cleared with dithranol, he or she is likely to experience a period free of psoriasis ranging from four to six months, before the plaques gradually come back. Sometimes the remission lasts for one to two years.

The disadvantages of dithranol are that it is very time-consuming and rather messy. People in certain jobs find that it is difficult to continue working while using dithranol

– for example, in manual labour, sweating may cause the dithranol to spread onto normal skin, where it may cause soreness. Dithranol may also be difficult for people who have to wear a suit for work.

There are two main side effects of dithranol: neither is serious, but both limit its use. Dithranol can stain the plaques and irritate and stain the surrounding skin. The purple–brown discoloration of the skin tends to peel off after a few days, but the staining of clothes, bathtubs and other objects touched by the skin may be permanent.

Irritation and burning of the surrounding skin can be controlled by beginning with the weakest concentration of dithranol and increasing the strength every one to two days. The starting concentration is usually about 0.05 per cent, gradually increasing up to three to five per cent in some patients.

As a result of the staining and possible soreness, attempts have been made to produce chemicals that still have similar benefits to dithranol but without these side effects. These attempts have not been very successful – the newer products tend to have fewer side effects but also seem to be less effective. To gain the full benefit from a 24-hour application of dithranol, staining almost always occurs, although the irritation and burning can be kept to a minimum by carefully adjusting the concentration according to the response.

Ultraviolet light

Most patients with psoriasis find that sunlight helps their condition. In fact, for many, one to two visits a year to a sunny climate will work wonders for their skin. The sun emits energy in the form of ultraviolet rays, which are invisible to the naked eye. These rays can be divided into three forms, depending on their wavelength: UVA (315 to 400 nanometres), UVB (280 to 315 nanometres) and UVC (100 to 280 nanometres). Most rays are UVA, which has the longest wavelength and penetrates deepest into the skin. UVB rays have a shorter wavelength and are more intense, but penetrate the skin less deeply. UVC rays are the shortest and are lost in the atmosphere before they reach Earth.

UVB phototherapy

UVB rays are the cause of sunburn. They are beneficial in psoriasis and can be artificially produced by sunlamps. The use of these sunlamps in psoriasis is called phototherapy.

Broad-band UVB phototherapy can be used on its own, particularly in guttate psoriasis. The treatment is usually given three times a week, although it can be given daily. However, UVB phototherapy is more usually combined with dithranol in the Ingram regimen or with tar in the Goeckerman regimen. It can also be used in conjunction with oral retinoid drugs (acitretin) or with topical vitamin D analogues (calcipotriol or tacalcitol).

TL-01: narrow-band UV at 311 nanometres

Phillips have devised lamps that seem to be more effective than broad-band UVB at clearing psoriasis. These narrow-band lamps are gradually taking over, as hospitals replace their broad-band UVB units. The narrow-band UV lamps can also be used with other treatments as mentioned under UVB phototherapy.

The Psoriasis Treatment Centre at the Dead Sea, in Israel, reports that three-quarters of patients improved by 90 per cent or more after four weeks of treatment. It is likely that UVB rays are the main reason for this benefit.

Psoralens and UVA photochemotherapy (PUVA)

Certain chemicals from plants (especially from Ammi majus) called psoralens seem to benefit psoriasis if they are used after the skin has been irradiated with long-wave UVA light. The psoralens are most effective when they are taken orally, although they can also be used on the skin itself or in the bath. The interaction of psoralens with UVA is known as PUVA or photo-chemotherapy, and has been used since the mid-1970s. PUVA is a highly effective treatment for widespread plaque psoriasis. In some centres, the psoralen is taken orally two hours before UVA exposure, and in other units, it is added to a bath that is taken immediately before UVA exposure. There are two types of psoralens used in PUVA treatment. Some patients experience nausea after taking 8methoxypsoralen. If this is the case, 5-methoxypsoralen – a different, equally effective form that doesn’t have this side effect – can be used.

In most centres, the treatment is undertaken twice a week. About 90 per cent of patients will clear completely in six to eight weeks. During treatment, the skin usually becomes tanned. The clearance that results will last, on average, for four to six months before the psoriasis gradually returns. However, in some patients, the psoriasis may come back straight away whereas, in others, it will take years to return.

PUVA is most effective in widespread plaque psoriasis, but it can be used in pustular psoriasis (generalised and localised, involving the palms and soles), and in erythroderma. However, in these types of psoriasis, there are alternative treatments that may be more effective. PUVA is not effective in the scalp or flexures.

In many centres, a retinoid drug (acitretin) is given for ten days before PUVA and continued right through the PUVA course. It has been shown that only about half the exposure to UVA is required when the treatment is combined in this way.

The immediate side effect from PUVA is burning from the UVA rays, so the starting dose of UVA is usually low and is then increased gradually. There has been anxiety that, in oral PUVA, where the psoralen is taken by mouth, cataracts may develop. There has, however, been no clinical evidence of this, although, as some initial reports suggested the possibility, patients are all required to wear special protective glasses from the moment they take the drug and for the rest of that day. They are also required to wear special protective goggles while in the UVA treatment unit.

The main concern with PUVA is an increased risk of the development of skin cancers. This is a dose-related effect, so the more exposure to UVA the greater the risk. Fortunately, the risk is largely of the relatively easily treated non-melanoma skin cancer and not melanoma itself. Patients who have had high-dose PUVA (more than 300 treatments) have a sixfold increased risk of developing skin cancer when compared with low-dose PUVA patients (less than 160 treatments). Fair-skinned people have twice the risk of skin cancer compared with dark-skinned people.

Recent guidelines from the British Association of Dermatologists and the Royal College of Physicians suggest that the lifetime maximum of PUVA treatment should not exceed 1,000 joules per square centimetre (J/cm2) if at all possible. This is the equivalent of about 100 PUVA treatments or about six to eight courses. However, for people who find that PUVA is effective, once they have had 1,000 J/cm2 of energy of UVA, there would need to be a full discussion as to the relative risks of continuing further PUVA or switching to alternative treatments, which may also have side effects.

The risk of skin cancers appears to be greater on the male genitalia and therefore these should be covered during treatment. The face should also be covered unless it is affected by psoriasis, to prevent additional photoageing of the skin. There is no evidence that bath PUVA has less risk of skin cancer, but eye protection is not necessary as very little psoralen is absorbed. Oral retinoids given at the same time as PUVA, may reduce the risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer.

Methotrexate

Methotrexate is an anti-mitotic (anti-cancer) drug and has been used extensively for psoriasis for more than 30 years. It inhibits DNA synthesis, and so slows down the epidermal cell turnover. Methotrexate works to a certain extent on all rapidly dividing cells, including blood cells, so regular blood counts are important to ensure that there are no adverse effects on the blood. Methotrexate also affects the immune system abnormalities found in the skin of people with psoriasis.

Methotrexate is mainly used for severe psoriasis. It is highly effective in plaque psoriasis and is well tolerated; it also has a role in psoriatic erythroderma, generalised pustular psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles.

Methotrexate is usually given orally, but can also be given by intramuscular injections. The dose varies from 5 to 25 milligrams per week, although it is usually between 10 and 15 milligrams a week. Methotrexate is usually given as a single weekly dose, rather than several daily doses, as the side effects on the liver (see below) are reduced when the drug is given in this way.

Side effects of methotrexate

• Nausea:

This is not usually a problem, but is occasionally the reason for stopping treatment.

• Blood:

Methotrexate may cause bone marrow suppression, which can lead to anaemia, bruising and an inability to fight off infections properly. As a result of this, regular blood tests are required (usually weekly at first) and later every 10–12 weeks.

• Liver:

Methotrexate can produce potentially serious and irreversible liver damage. However, when used in low doses and given weekly, the risk is low. Moreover, if alcohol intake is kept to a minimum, so as not to put a strain on the liver (not more than one to two units of alcohol a week), liver damage is rare. The liver function is checked regularly with a blood test.

Unfortunately, the liver can be damaged considerably by methotrexate before the usual liver function tests in the blood reveal any abnormality, because these tests are not always sensitive enough. In many centres, therefore, intermittent liver biopsies are performed, so that early damage can be identified and methotrexate treatment stopped if necessary. Liver biopsies involve putting a needle into the liver to extract a small sample of cells for examination under a microscope. Many centres will perform a liver biopsy before starting methotrexate or once a patient has been cleared of psoriasis, and then every few years while they remain on methotrexate.

The necessity of liver biopsies is under debate. Most centres still do biopsies in patients aged under 65 to make sure that their liver is not being damaged. Rheumatologists, however, use methotrexate extensively for rheumatoid arthritis and most do not do liver biopsies. Liver biopsy is relatively safe, although it is an invasive test that can cause some internal bleeding, pain and a small risk of infection. It is performed under ultrasound imaging control to keep complications to a minimum.

• PIIINP:

The amino terminus of type 3 procollagen can be measured in the blood and recent work suggests that it is a good marker for liver damage from methotrexate. It is certainly more sensitive than the routine liver function tests. Many centres now rely on the PIIINP test and perform liver biopsies only in those patients in whom the test is repeatedly positive. There is unlikely to be significant liver damage in a patient who has repeatedly normal tests.

• Effects on unborn children:

Methotrexate is a teratogen, which means that it can damage a developing baby if it is given to a pregnant woman. Therefore, women should not become pregnant while taking the drug. Men on methotrexate should also take care not to get a woman pregnant, because the drug can pass into the sperm and damage the fetus.

• Kidney function:

Methotrexate does not damage the kidneys, although it is excreted (removed from the body) by them. It is important to check kidney function with a blood test at the start of treatment. If patients are on methotrexate for many years, annual blood checks are essential. Kidney function slowly deteriorates with age. If it is not checked regularly, methotrexate levels may rise in the blood and cause more side effects on the bone marrow and the liver. It may be necessary to reduce the methotrexate dose as years go by.

• Drug interactions:

Methotrexate can interact with other drugs – it can make another drug more toxic by increasing its blood levels. This is particularly common with aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Therefore, if you are taking methotrexate, tell your doctor or pharmacist, so that he or she can assess the risk of drug interactions.

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is also an anti-cancer drug. It is much less popular than methotrexate but has a role in the treatment of psoriasis because it is moderately effective and does not damage the liver. Hydroxyurea is more likely, however, to cause bone marrow depression, so blood tests need to be performed more frequently than with methotrexate. Patients may also have a slightly lowered white blood cell count. Hydroxyurea is often best used in conjunction with the retinoid drug acitretin. It is given in a daily oral dose of between 0.5 and 1.5 grams. As with methotrexate, women should not get pregnant, and men should not father children, while taking hydroxyurea.

Oral retinoids

Retinoids are vitamin A drugs with the chemical name of tretinoin or isotretinoin. Acitretin is the main retinoid used in the treatment of psoriasis and is taken orally in a dose of 25 to 50 milligrams a day.

Retinoids have many effects on the skin. In particular, they promote epithelial cell differentiation, which means that they encourage skin cells in the epidermis to mature properly instead of reaching the skin’s surface before they are fully formed.

On its own, acitretin is often only partially effective in plaque psoriasis. It is, however, particularly effective in generalised pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles, and in unstable forms of psoriasis. Acitretin is often combined with other treatments such as PUVA, UVB phototherapy or hydroxyurea, and can also be combined with topical treatments such as vitamin D analogues. Acitretin can be used in children.

Side effects of oral retinoids

• General:

The skin often becomes dry and the lips may crack. The eyes and nose may become dry too. Occasionally, hair loss occurs, although this reverses once the drug has been stopped.

• Cholesterol and triglycerides:

Retinoid drugs tend to raise cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the body, so these will need to be checked occasionally. It is worthwhile controlling your intake of dairy products while on retinoids to reduce the chance of an elevation of your blood lipids.

• Liver:

Very rarely, acitretin or retinoids cause inflammation of the liver (hepatitis).

• Bony and soft tissue changes:

These changes are usually without symptoms and are therefore picked up only on an X-ray. Calcification may occur in the anterior spinal ligament. Other X-ray changes can occur but are of doubtful clinical significance.

• Teratogenicity:

Women on retinoids must not get pregnant for two years after the course has been completed, as retinoids can cause birth defects. Although most of the acitretin is promptly excreted, it can be bound in fat for up to two years. The chance of having an abnormal child if a woman takes acitretin during pregnancy is extremely high. Men can father children while taking acitretin.

Ciclosporin A

Ciclosporin is developed from a fungus called Tolypocladium inflatum gams. It is an immunosuppressive drug and is used to control and prevent rejection of transplanted organs. In small doses, ciclosporin A is very effective in controlling psoriasis, by affecting the T cells, rather than by preventing the division of skin cells and their rapid turnover. Ciclosporin is given daily in doses of approximately three to five milligrams per kilogram of bodyweight (150 to 400 milligrams) orally in two divided doses. Ciclosporin A is well tolerated.

Side effects of ciclosporin A

• Excess hairiness:

Unusual in the low doses that are used.

• Gum:

Thickening of the gums may occur, but this is unusual in the low doses used.

• Gout:

Occasionally, ciclosporin A can elevate uric acid levels, causing gout.

• Renal function:

Although ciclosporin A is used in renal transplant recipients, it can actually damage the kidneys. This needs to be monitored by monthly blood tests. The drug is discontinued if tests show that renal function has altered by certain recognised parameters.

• Hypertension:

A rise in blood pressure can occur with ciclosporin A so it is important that the blood pressure is checked monthly. Hypertension is independent of its effect on the kidneys. A mild elevation of the blood pressure does not mean that ciclosporin A has to be discontinued – treatment for the blood pressure can be introduced if necessary.

• Long-term use of ciclosporin A:

Long-term use can lead to skin cancers induced by ultraviolet light so it is particularly important that people on ciclosporin A are given advice about sun protection.

• Other considerations:

If you are taking ciclosporin A, you need to be wary of taking other oral drugs

at the same time, as drug interactions can occur. For example, anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Brufen or Voltarol, which are used for aches and pains, can increase the amount of ciclosporin in your blood. This is because your kidneys’ ability to get rid of the ciclosporin is diminished by the anti-inflammatories. If you are on ciclosporin, make sure that your doctors and pharmacist are aware of this before they prescribe/dispense another medicine for you.

Tacrolimus is similar to ciclosporin A. It is an immunosuppressive in patients who receive a transplant and in those with psoriasis. Tacrolimus is not effective in plaque psoriasis when used topically.

TREATMENT OF DIFFERENT TYPES OF PSORIASIS

Scalp psoriasis

The treatment of scalp psoriasis is not always easy. For mild cases, in which the plaques are not lumpy or very scaly, a tar shampoo may be all that is required. Topical corticosteroids are often effective and the hairy scalp seems to tolerate them quite well without much thinning of the skin. However, they should not be used continuously.

For more severe psoriasis of the scalp with many lumpy lesions, the treatment is more difficult. The first thing is to remove the scale and so flatten the lesions. This can be done with salicylic acid products, of which there are many formulations. These products are often combined with tar, so they can be messy to use. However, if they are massaged well into the scalp and left on for some time (preferably hours), they will gradually remove all the scale, with the hair left intact. Another option is to use arachis oil, which is possibly less messy and non-smelly. Afterwards, the choices to keep the psoriasis from building up again include topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues (calcipotriol scalp solution) or possibly just a tar shampoo. Most patients with scalp psoriasis can keep it under reasonable control, but it is often difficult to clear it completely. It is not usually severe enough, however, to consider systemic treatment with agents such as methotrexate, retinoids or ciclosporin A. PUVA is of no help if the scalp is hairy.

Nail psoriasis

There is no treatment that is effective when used topically for nail psoriasis. If a patient has severe enough psoriasis elsewhere to warrant systemic treatment, then the nails may improve.

Pustular forms of psoriasis

Pustular psoriasis is most common on the palms and soles, but can occasionally occur in a severe form of generalised pustular psoriasis.

• Localised pustular psoriasis on the palms and soles:

This can be very difficult to treat. Topical corticosteroids are ineffective, unless very potent products are used with the risk that thinning of the skin may occur. Dithranol is usually ineffective and is messy to use at these sites. Vitamin D analogues are only occasionally effective. For mild cases, moisturisers with the occasional use of a potent topical corticosteroid or possibly a vitamin D analogue are the best options. Dovobet can be tried, but remember that it contains a potent corticosteroid and so must be used intermittently. For the more severe forms, PUVA, methotrexate, hydroxyurea, with or without acitretin, and ciclosporin A are all helpful. However, potential side effects of these agents have to be balanced against the severity of the disorder.

• Generalised pustular psoriasis:

Acitretin, ciclosporin A, methotrexate and occasionally PUVA are all effective in this rare form of psoriasis.

NEWER TREATMENTS

Fumaric acid esters

These have been used in parts of Europe and especially Germany for 25 years, but so far they have not been studied much in the UK. There is no product licence for these products in the UK. The benefits are partially via the effects on the immune process and partly via keratinocyte proliferation. They seem to be relatively safe and effective and it is hoped that these products will be studied more in the UK.

Mycophenolate mofetil

This drug has been studied for its effect in psoriasis and it probably has effects on both the immune process and the keratinocyte proliferation. It can suppress the bone marrow and so regular blood checks are required. It is effective and relatively safe.

Biologics

There are now several products that have been developed and are being studied intensively which attack the various specific immunological abnormalities that have been found in psoriasis. They block various chemicals called cytokines, which are released in psoriatic lesions. Several of them (adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab) have already received a licence for plaque psoriasis, but etanercept is the only one to have received a licence in the UK for this use.

There are, for most patients, good and effective topical and systemic treatments for plaque psoriasis and the new biologics are not as effective, giving a satisfactory response in only about 30 per cent of patients, although the response is higher, at 80 per cent, with infliximab. The latter does not have the highest response rate, but antibodies to it are formed and so reactions to it can occur and its effect can be lessened over time, leading to higher doses being needed.

In psoriatic arthritis, where the treatment options are much more limited, the biologics will have a much clearer role. They are potent immunosuppressants and infections can be a problem, and there is worry about long-term cancer risks. They are hugely expensive (about £7,000 to £14,000 per year to treat each patient, at 2004 prices). They do not cure psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis and so have to be continued. They are all given by injection, but some can be given by the patient him- or herself subcutaneously (just under the skin), whereas others need visits to hospital for the injections. All need some blood monitoring.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) is due to report on these biologics in autumn 2005.

The biologics are an exciting development and it is likely that their main use will be in psoriatic arthritis, although in patients with plaque psoriasis consideration would be given only in patients who had failed to respond to topical or conventional systemic agents or in those patients who had developed side effects with such treatments.

PSORIASIS AT DIFFERENT AGES

It can be very hard for parents to cope with seeing their children distressed because of a skin condition. Any child with an obvious skin problem may be subjected to teasing or even bullying, and parents and teachers must be particularly vigilant in looking out for this. It is worth talking to their head and class teacher to ensure that the pupils and teachers understand that psoriasis is not infectious. The Psoriasis Association can be particularly helpful in putting children with psoriasis in touch with others with the condition. It is also vital that your child understands his or her own condition and treatments, and that the explanation that you give is appropriate for the age. You may want to do this together with professionals in the field.

Most children with psoriasis will respond to topical vitamin D drugs, short-contact dithranol or long-contact dithranol, all with or without UVB phototherapy. Most doctors are reluctant to use PUVA in children because there is an upper limit of lifetime exposure to UVA rays to prevent an increased risk of skin cancer.

Fortunately, plaque psoriasis is rarely so severe in children that systemic treatments such as methotrexate, retinoids and ciclosporin A are required. Methotrexate is very rarely used in children because of the increased risk of liver damage with cumulative doses. Doctors are also reluctant to use prolonged courses of potent topical corticosteroids in children because of the thinning effect on the skin and possible formation of striae (streaks on the skin).

In elderly patients, it is important to remember that eczema and psoriasis are often confused. It is also essential to be particularly careful when using dithranol, topical retinoids or vitamin D drugs because they can all irritate the skin. Moisturisers are often very helpful and can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroid ointments. A mild-to-moderate strength corticosteroid will often be adequate.

In elderly patients with widespread psoriasis, doctors often choose to use methotrexate, PUVA, hydroxyurea or ciclosporin A, especially if such a patient would find it difficult to attend an outpatient treatment unit on a regular daily basis.